Jim Klinger, Concrete Construction Specialist

The Voice Newsletter June 2024

Full disclosure: I received a call a few days ago from a former co-worker who is nearing retirement. Both of us started working concrete construction in the 1970's We spent some quality time on the phone looking back on our years in this tough business of ours. We talked as old men do. We first met on a large public works job in 1992, one of ASCC member Conco's first major projects as a GC in our market. At that time, Matt Gonsalves (1930-2018) was one of the original founders of the Conco Cement Company--and also its President. One thing that stayed with us both over the years is the set of rules Matt established--and lived by--whilst building a wildly successful concrete construction company along with his son--current President--Steve Gonsalves.

One way or another, almost every single column or magazine article I write falls back somehow to Matt's Rules. What you are about to read in the ASCC Hotline call account below is a fine example.

"Matt's Rules for Success"

- "Be safe. This is the prime directive. Safety pays".

- "Have fun. If you aren't having fun, find another business."

- "Make money. That's why we do what we do."

- "Keep the money you just got done making."

- "You always have to try to position yourself to get lucky."

- "The harder you work...the luckier you get."

- "Sometimes you have to eat a mile of excrement. But once you got it eaten...baby, you got it made."

__________________________________________________________________

Question: We are attempting to wrap up the reinforced concrete portion of an affordable housing apartment complex featuring an elevated post-tensioned (PT) concrete slab one lift above street level at the so-called "podium" level. The podium slab serves as the foundation platform for 7 stories worth of wood "stick framed" construction above. Since affordable housing is a scarce commodity here in our real estate market, the project was fast-tracked by the City (including construction financing) and advertised for bid without project specifications. The only documents our estimators had to work with at bid time were the Level 3 D-D (design development) set of structural and architectural drawings, the geotechnical report, and a preliminary project schedule.

This project is typical of hundreds of such podium structures we have built over the years: 50,000 square foot (SF) footprint, 36-inch-thick foundation mat, and either cast-in-place (CIP) concrete or shotcrete basement walls supporting an elevated PT slab at grade (e.g. street level) and another elevated PT podium slab one lift above grade.

Late last fall, the jobsite was excavated 3 feet wide of the building footprint by the earthwork subcontractor--who sloped the bank sides back to allow our crews safe access all the way around the building to erect, strip and patch the perimeter basement walls.

Because our company has such a familiarity with the typical structural framing of a podium-type reinforced concrete structure, we were very comfortable pricing the work despite being furnished incomplete construction documents. We also knew that our two competitors for this same project were working from the same D-D documents. In other words, we were bidding on a level playing field.

Unfortunately, once our contract was signed, the playing field tilted...and things started rolling south from there. While it is true that we had ample experience with the concrete scope of work, we had zero experience with our customer--the general contractor (GC)--or their fresh-out-of-school project engineer assigned to oversee our concrete scope of work.

The construction sequence was partially dictated by the design team. Once the first lift of perimeter CIP walls supporting the street-level PT slab was completed, the designers required the entire street-level slab to be placed, stressed, and up to full strength before application of outside wall face waterproofing--and subsequent backfilling to grade shortly thereafter--could safely begin. And therein lies our problem.

Part of our standard scope of work includes patching of the formed faces of our concrete walls. This task must be completed before the follow-on waterproofer can install his work. Our standard operating procedure is to send our patch crew right behind the stripping crew--same day--which is what we did on this job. The patching was completed in late February. Due to seasonal monsoon rains, all earthwork operations were delayed--including the backfill behind the perimeter CIP walls. The GC informed us the waterproofing installation activities were going to be on rain delay as well.

In the meantime, we recently completed the podium slab and submitted our final progress billing--along with a request for partial release (50 percent) of our retention as well.

Instead of receiving payment, the GC has just put us on notice that we are in danger of delaying the project. The waterproofer had mobilized, examined the perimeter wall surfaces, and announced to the GC that they refused to start installation until the concrete wall surface substrate had been prepared to their satisfaction. The GC is telling the project Owner that the waterproofing manufacturer will not provide the warranty if their product is installed over the existing concrete substrate.

We reminded the GC that our patching was completed months ago consistent with the formed surface tolerance requirements of concrete industry standard ACI 117-10: Specification for Tolerances for Concrete Construction and Materials. In response, the GC sent us a copy of a generic "waterproofing at exterior wall detail" from the architectural drawings and rejected our argument as follows:

"Your subcontract is not based upon CIP (cast-in-place) tolerances. Nor is there any reference to that in the contract. The contract is based upon the approved plans that were given to you...please see attached detail to finish your scope of work...prompt action is required so that there are no further delays".

We are confident we are doing the right thing here, and that our work already meets the contract quality requirements and was completed in a timely manner. Is there anything the ASCC Hotline can offer to help support our position?

Answer: The GC's project engineer was quite correct...until he got it wrong, that is.

In order for the ASCC Technical Division to get to the bottom of this one, we first need to recognize there were some serious miscues on this project--on both sides of the aisle--which occurred even before you got to project Day 1. Let's look at those miscues first.

While it is true that your bid proposal letter states plain as day that your price quote is based on incomplete construction documents (e.g. no specifications), there is no evidence of follow-up on your part during the negotiation of your contract scope of work (aka "Exhibit "B"). Exhibit B is a significant section of the contract document where the quality expectations for the finished product must be clearly spelled out. In other words, anyone who reads your contract must understand straightaway what you owe the project. When we examined your Exhibit B, we found it silent on all matters related to concrete quality.

Another booby trap we found is the following clause in your contract that is a classic set-up gambit for the Owner's rep to raid your pocketbook at will:

Any time you see a "to the satisfaction of" clause in contract language (or in a specification section) it should serve as a red flag warning for you to grab your red pen and strike the clause from the document before signing. While this particular contract clause is not referenced in any of your project correspondence we reviewed, it is still there--waiting to be discovered--perhaps during discovery should things on your project head further south.

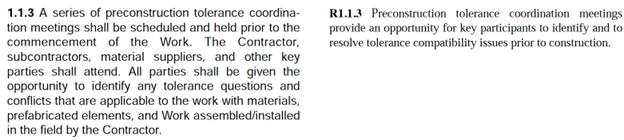

Another significant miscue on the part of all of the contractors (that includes concrete, waterproofing, and GC) is that there was no preconstruction tolerance coordination meeting--a mandatory requirement specified in ACI-117--where quality expectations at hand-off from one trade to the next must be discussed among all stakeholders and agreed to. Such meetings in advance of the work are essential to ensuring a successful project.

Knowing the above, we can now rinse out the evidence and determine what you really owe the project.

When your GC tells you that "your contract is not based on CIP tolerances,” the casual observer might just be inclined to agree, since there is no explicit mention of ACI 117 (or ACI 301, for that matter) anywhere in the construction documents.

This is unusual to the degree that almost all projects we review here at the ASCC Technical Division feature specifications drawn from AIA Masterspec, which appears in contract specification documents typically as:

In the cases where AIA Masterspec is used, references to ACI 117 tolerances are either explicitly stated as above or such references are given within the ACI 301 document. Either way, you are covered. Unfortunately, since your project is one of the few that has proceeded without benefit of reference documents (or specifications at all), we must search elsewhere to find what tolerances you owe the project.

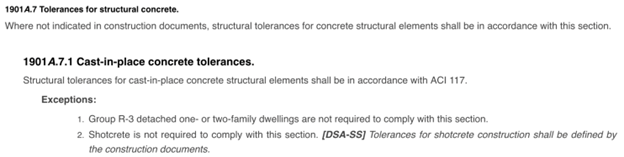

The answer lies hidden within your structural drawing "General Notes" --in the "Project Information" section that identifies the basis of the structural design. According to ACI 318-19: Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete, section 26.2.1 requires the construction documents to identify the "Name and year of issue of the Code, general building code, and any supplement governing design.” In your case, the general building code listed is the 2019 edition of the California Building Code (CBC). When you signed your contract in June 2023, the

2019 CBC had already been superseded by the 2022 edition, where we find the following in Chapter 19:

In plain language, what this means is that if the designers did not specify any tolerances for the structural reinforced concrete scope in their construction documents, then by default the tolerances specified in ACI 117 automatically kick in. As you can see, this is a code requirement, not only in the CBC but in the International Building Code (IBC) as well.

__________________________________________________________________

Lesson learned #1: No matter what your bid proposal qualifications state, what you will be held to two years down the road from contract signing is the contract language itself.

Lesson learned #2: Remember the words of former ASCC Technical Director Bruce Suprenant: "Would you like to read your contract language before you sign, or would you like the opposing attorney to read it to you two years from now in deposition?"

Lesson learned #3: Never start work on a project before attending the mandatory tolerance coordination meeting specified in ACI 117-10 section 1.1.3 thusly:

It is in mandatory meetings such as this that important documents such as ASCC

Position Statement #27: Formed Surface Requirements for Waterproofed Walls should be reviewed and discussed among the stakeholders.

Lesson learned #4: Become familiar with what reference documents are and how to handle them to protect yourself from unfair (and costly) risk. A good place to start is the article from which the above AIA Masterspec excerpt is taken, namely "ACI Reference Specifications: Consensus standards are designed for use in construction contract documents" by Bruce Suprenant, Concrete International, October 2019.

Lesson learned #5: Based on our Hotline call, a set of contract specifications (aka "project Manual") was never issued to the ASCC concrete contractor, which is consistent with the contract language excerpted above. It appears that the stakeholders on the Owner's side of the aisle did not consider such a document "applicable". This forces the concrete contractor to have a heightened awareness of risks associated with not only his work, but with all contiguous follow-on work as well.

What follows is an example from a totally different project that illustrates the simple fact that there is money to be saved (or made) by opening up the project specifications and taking a peek at what is contained in the other guy's playbook.

You always want to know what the other guy owes the project. This is one sure way to position yourself to get lucky.

An ASCC contractor reported a Hotline case very similar to that described above. The concrete had long been placed, and the contractor's retention request was returned with a substantial backcharge attached to it. This was a massive reinforced concrete parking garage, which featured a follow-on painted surface on all "exposed" concrete that could be seen when viewed from outside the structure. We are talking any beam sides, beam bottoms, parapet (crash) walls, columns, shear walls, and so on. If you could see it, it was fair game for paint. This was not an "architectural concrete" scope per se, but all stakeholders on the project knew before bid day that the architectural color renderings clearly showed the viewable, painted concrete surfaces and understood the architect's intent.

After the final concrete "catch-up" work (e.g. curbs, pads) was complete, the concrete contractor dispatched a crew to sweep each and every floor--even though not every bit of debris that ended up in the dustpan was generated by the concrete scope. The agreement was that the structure would be left "broom clean". Upon completion of this final contract scope activity, the architect, GC, and concrete contractor attended a final job walk. The architect and GC complimented the ASCC concrete contractor on another job well-done.

Fast-forward six months. Since retention payment was contingent on all other portions of the project being complete, retention checks were on the near horizon. The painter was one of the last subcontractors to perform work on the jobsite.

By that time, the familiar GC onsite management staff had all been transferred to other projects. Most of the jobsite trailers were gone, and the GC imported someone from another project to herd-dog the final punchlist items and close the job out.

At some time during the painter's work, complaints were made to the new GC rep that the painter was having to perform undue surface preparation before the paint could be applied. Disputed items included removal of efflorescence due to seasonal monsoon rains, minor amounts of mortar leakage at beam-column connections, and so on. The painter convinced the new GC onsite rep the "extra work" was legitimate, and--between the two of them--documentation and cost tracking for backcharge purposes began in earnest. The concrete contractor was never called to discuss the disputed surface preparation claims.

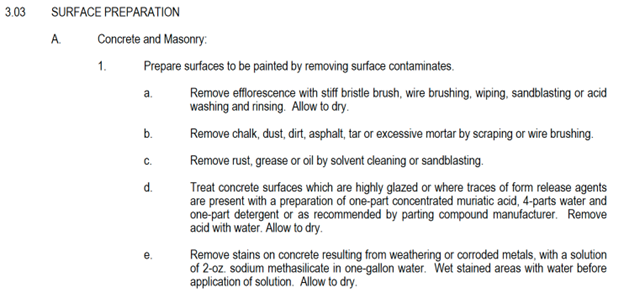

The ASCC member called the Hotline, wondering how on earth a structure that had been complimented by both the architect and GC a few months earlier could now be such a disaster for the follow-on painter. That is when the Hotline took a look at the other guy's playbook (aka the Division 9 specifications). Here is what we found that clearly spelled out the surface preparation scope that the painter owed the project all along:

As you can discern plain as day, neither the painter nor the new GC onsite rep had any idea that section 3.03 existed--or what it contained. Unfortunately, ignorance of what is contained in construction documents (and their reference documents) seems like a costly, unforgivable epidemic in the construction industry today.

(N.B. Some may argue that the painter's estimator read section 3.03 (above) and excluded such surface preparation from their Division 9 scope of work. If that was the case, where was that work transferred? By all rights, it was the GC's responsibility at bid time to find a home for the surface preparation, and to advise the new owner of that scope so it could be incorporated--and priced. No such notice of scope transfer was ever given to the ASCC member at bid time. As it turned out, we were given an opportunity later to view the paint subcontractor's Exbibit B, which did not mention exclusion of the section 3.03 surface preparation work. (No question-the painter owned surface preparation as specified.)

In our experience, it is highly advisable for the concrete estimator to grab the specifications during bid time and perform what we refer to as an "oddball run.”

This is where we look at the odd-numbered specifications only, starting with Division 1 (General Requirements), then division 3 (Concrete), then division 5 (Metals), then division 7 (Waterproofing), then division 9 (Finishes), and then...all the way at the back of the book...division 31 (Earthwork). By this time, the estimator should know the job well enough to determine if performing such a potential risk review in other playbook divisions is warranted.