Jim Klinger, Concrete Construction Specialist The Voice Newsletter October 2023

Full disclosure: Sometimes it takes a bit of background confected with lore borrowed from other structural building trades to help illustrate obliquities particular to our own concrete trade. As it turns out, this right here is a classic example of that.

To oversimplify enormously, any time a licensed design professional (LDP) prepares the structural design of a steel building frame featuring composite concrete slabs on metal deck (SOMD), reference documents (e.g., applicable building codes) from local or regional jurisdictions and at least 4 national governing standard organizations are generally consulted as follows:

The American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC), whose Code and Specifications govern the design, fabrication, erection, and retrofit of structural steel columns, beams, and other shapes.

The Steel Deck Institute (SDI), whose Code and Standards govern the design, sale, purchase, manufacture, and installation of composite steel deck-slabs (aka "slabs on metal deck" aka "SOMD").

The American Welding Society (AWS), whose Codes and Standards govern the design, prequalification, and inspection of all welds, including welded splices of certain grades of reinforcing steel and headed steel studs.

The American Concrete Institute (ACI), whose Codes and Specifications govern the design of most structural concrete, including slabs on metal deck when specifically called out as "reinforced concrete" (ACI 318-19, section 1.4.10).

Armed with this modest library of background information, we can now view the first of this month's ASCC Hotline topics through a custom lens...call it adjusted for perspective...and down into the rabbit hole we go...

______________________________________________________________________________

Question: We are a concrete subcontractor working on a 20-story high rise project featuring structural steel framing and unshored composite slabs on metal deck (SOMD). As of today, our portion of the project work is approximately 5 percent complete. All steel framing, metal decking, reinforcing steel, and construction joints are furnished and installed by others. Our subcontract work was bid as a discrete "P-P-F" scope (pump-place-finish only) which actually also includes ready mix concrete purchase and one application of spray-on curing compound before our finishing crew leaves the jobsite. As can be seen below in our bid proposal line item #22, we also include blow-off of the metal deck substrate prior to concrete pours:

[Based on several unsavory and very costly experiences on past SOMD projects, our company bid policy now dictates that we call special attention to--and exclude--handling any debris generated by the Division 5 trades simply due to the sheer weight of the debris (steel is more than 3 times heavier than concrete) and the awkward logistics required to collect and transport such heavy spoils to dumpsters, usually located on the ground.]

Since we are not mobilized on site full time, a typical SOMD placement operation actually starts for us just after lunch on the day before we are scheduled to place concrete. We dispatch our finisher foreman and a small crew to walk the pour area with the general contractor (GC) representative to discuss logistics and expected slab finishes, review survey results (survey performed by GC personnel) showing the as-built elevations of the metal deck and structural steel substrate, set our finishing screed pins (we generally place SOMD to a uniform gauge thickness and state as much in our bid proposals) and begin our pre-pour clean up. And it is the cleanup part where--despite our bid exclusions highlighted above-- things can still get messy.

When we begin our pre-placement walk-through, the work is still in progress. Electricians are running conduit, plumbers are setting cans, sheet metal workers are framing metal deck blockouts, ironworkers are placing rebar, and so on. By all rights, these trades should be 100% complete by the end of the day, including cleanup of all trade-specific trash and debris each trade has generated. In theory, the inspector should be able to complete the pre-pour checklist in reasonably comfortable fashion.

Unfortunately, in the concrete business, things happen. Concrete activity durations leading up to a placement can become squeezed, causing our cleanup crew to end up being chased by the concrete bucket. And just when we thought we had the whole routine outsmarted.

To make a long story short, here is the reason for this Hotline call. The Owner's inspector usually assigned to our project was out on leave. On his inspection watch, removal of broken ferrules by the metal decker after the studs are inspected is a strictly enforced checklist item that must be completed before he will allow rebar placement to proceed.

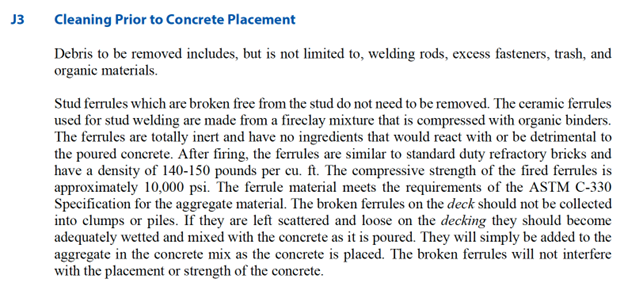

But the replacement inspector informed us that the broken ferrules did not need to be cleaned up at all. In other words, the inspector told our cleanup crew to just go ahead and let the broken ferrule pieces be incorporated into the slab concrete as long as the ferrules were spread out and not grouped into piles on the deck. All other debris, however, had to be cleaned up as before.

[N.B.: In theory, headed studs (aka "shear connectors") can be fillet welded via traditional arc welding to the top flange of a steel beam to ensure the steel beam/metal deck/concrete SOMD truly act as one composite structural unit. But fillet welding is too slow. Instead, the studs are shot through the metal deck and fused to the top of the steel beam flange supporting the deck. In that case, special vented ceramic through-deck ferrules (aka "arc shields") are placed at the bottom of each stud. The refractory properties of a vented ceramic ferrule allow the weld metal to be contained while at the same time allowing zinc and other contaminants produced by melting the galvanized metal deck to escape the weld puddle zone at the base of the stud. Once cooled, the ferrules are broken off to allow visual inspections to verify a full 360-degree weld flash and allow subsequent hammer/bend testing to proceed. The broken ceramic pieces can then be collected and discarded. In theory, of course. See photograph below showing shot-on studs, sheet metal decking material, and broken ferrules.]

photo credit: Sino Stone. Note contaminant exhaust vent pattern at base of stud.

So that is how it went until yesterday--a pour day--when the original inspector returned to work and saw the metal deck substrate littered with broken ferrules at the same time our crew was assembling the last sections of pump system. In order for the inspector to allow the pour to go forward, the GC paid our crew to clean up the broken ferrules. We can only assume the GC then passed the cost on to the metal decker via a backcharge.

So, the Hotline question then becomes..."Which inspector has it right?" Going forward, we don't want to get caught up in last-minute labor scrambles to mitigate cleanup responsibilities owned by a division 5 trade.

Answer: The Owner's replacement inspector is correct. According to the latest governing SDI document (SD-2022 Standard for Steel Deck, page 90), broken ceramic stud weld ferrules can remain on the deck and be incorporated into the pour for reasons stated in section J3 below:

This is a great example of Division 5 cleanup line items that really need to be included in bid proposals and preconstruction meeting agendas on every SOMD project. Thanks to ASCC member Chris Garcia of DPR for helping to research this issue.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Question: We are in the preconstruction submittal phase of an above grade, mid-rise reinforced concrete office building project under private ownership. This is no exposed architectural concrete masterpiece headed for the winner's circle at the ACI Excellence in Concrete Construction Awards Gala. This is a simple concrete box where--once in service-- all the concrete surfaces will actually be concealed by the work of follow-on trades. We're talking about dropped ceilings, tiled floors, furred columns, and a curtain wall skin. When we made our first round of reinforcement placing drawings, we attached a companion submittal package that included the manufacturer's cut sheets for all the standard reinforcing steel accessories we routinely use in our construction market e.g., tie wire, slab spacers, beam bolsters, bar chairs and precast concrete dobies. The architect rejected the use of the dobies on the grounds that the following project specification allows only metal or plastic rebar support material to be used in the work:

We could not find an ASCC Position Statement that addresses this topic. Is there anything in the ASCC Technical Division library that we can use to argue that the precast concrete dobies should be accepted?

Answer: There are several arguments that could be made to support your case, especially if the sole reason for rejection is "just because" it does not meet the specification without any further explanation or qualification. (We understand that the architect did offer the explanation that no one in their office had ever seen dobies used on past projects.)

First, the project specification does not say that precast concrete dobies cannot be used.

Second, by simple reference elsewhere in your Division 3 specifications, the work in your concrete scope is governed by ACI 301-20: Specifications for Concrete Construction, section 3.2.1.8: Reinforcement Supports, which states "Provide reinforcement support types within structure as required by Contract Documents. Reinforcement supports shall conform to CRSI RB4.1."

(N.B. The Concrete Reinforcing Steel Institute (CRSI) document referenced above is RB4.1-2022: CRSI Standard for Supports for Reinforcement Used in Concrete, which states in section 1.1.1 "This specification covers the design, use, material, and minimum performance requirements of reinforcement supports used in concrete to support various types of reinforcement, including but not limited to plain and deformed reinforcing bars, prestressing steel, post-tensioning tendons, steel wire and plain and deformed steel welded wire reinforcement." As it turns out, precast concrete dobies are manufactured in all shapes and sizes, many of which are displayed and discussed in RB4.1. In similar fashion, the CRSI Manual of Standard Practice defines "Dobies" in a roundabout way as follows:

It should be a simple matter, then, to demonstrate to the design team that the use of dobies is in fact an accepted standard concrete industry practice. Given the fact that the concrete surfaces on your project will always be hidden, it should not be difficult for the architect to reverse the call and accept your proposed use of dobies.

Here at the ASCC Technical Division, we have seen cases where dobies may not always be the best choice of bar support. We have seen dobies crushed under the weight of heavy mat slab reinforcement, which usually doesn't occur until the outermost layer of top bars are being placed, and by then it's too late for an easy fix. We would also stay away from the risk of using dobies in architectural concrete work, especially when the design team has specified the bar supports reasonably well in this example specification:

______________________________________________________________________________

Question: We are working on a pump-place-finish only (P-P-F) project where we carried the cleanup of pour areas prior to concrete placement in our bid proposal. By the time we mobilize on the jobsite, all the reinforcing steel has already been placed and secured by others. It is then up to our crew to pick up sawdust, loose trash, and debris through the layers of rebar; either with a backpack vacuum or some kind of home-made device (e.g., "a chingaderas") invented on the spot to snag those hard-to-reach items. We find ourselves fighting a constant battle with the inspectors regarding the debris generated by the reinforcing steel subcontractor, namely the rebar bundle tags and tie wire clippings. Is there anything in the industry literature that talks about who has ownership of such specific (e.g., not miscellaneous) trade debris? We know, for example, that painters are responsible for catching their spoils with a drop cloth they bring with them to the work. Is there a similar analogy that applies to the rebar trade?

Answer: This question is a perennial favorite here at the ASCC Technical Division. In our many years working with concrete, we have only found one "industry literature" mention of the tie wire clipping issue, namely in the textbook by Smith and Hinze titled "Construction Management: Subcontractor Scopes of Work" (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla., 2010). The following excerpt appears in Chapter 6- Reinforcing Steel:

A few years ago, we contacted the Concrete Reinforcing Steel Institute (CRSI) and asked them to weigh in on the question, "Who owns cleanup of rebar bundle tags and tie wire clippings?" The CRSI response was that there was nothing committed to print, but the accepted practice is for ownership of trade-specific cleanup items to be clearly addressed in contract scope language on a project-by-project basis. We have seen many rebar proposals, for example, where the rebar bidder assumes the cleanup of tie wire clippings due to normal rebar installation is excluded. Since there is no mention of the bundle tags in the proposals we reviewed, we believe that particular cleanup responsibility lies with the trade that cuts the bundles loose and generates the tags as debris e.g., the rebar installer.

We did hear of one instance where the tie wire clipping issue was the cause of jobsite arguments sufficient enough to bring the project owner to the table. The owner's inspector was demanding that all tie wire clippings be removed from the pour area before concrete could be ordered and placed. Both the concrete and the rebar subcontractors were refusing to clean up the clippings. To break the stalemate, the owner was told by one of the parties that the wire clippings actually constitute the addition of steel fibers into the concrete mix, a substantial benefit that was being generously supplied to the owner at no extra cost. Once the condition was reframed as a freebie, the owner agreed and settled the issue straightaway.

Full disclosure: Sometimes it takes a bit of background confected with lore borrowed from other structural building trades to help illustrate obliquities particular to our own concrete trade. As it turns out, this right here is a classic example of that.

To oversimplify enormously, any time a licensed design professional (LDP) prepares the structural design of a steel building frame featuring composite concrete slabs on metal deck (SOMD), reference documents (e.g., applicable building codes) from local or regional jurisdictions and at least 4 national governing standard organizations are generally consulted as follows:

The American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC), whose Code and Specifications govern the design, fabrication, erection, and retrofit of structural steel columns, beams, and other shapes.

The Steel Deck Institute (SDI), whose Code and Standards govern the design, sale, purchase, manufacture, and installation of composite steel deck-slabs (aka "slabs on metal deck" aka "SOMD").

The American Welding Society (AWS), whose Codes and Standards govern the design, prequalification, and inspection of all welds, including welded splices of certain grades of reinforcing steel and headed steel studs.

The American Concrete Institute (ACI), whose Codes and Specifications govern the design of most structural concrete, including slabs on metal deck when specifically called out as "reinforced concrete" (ACI 318-19, section 1.4.10).

Armed with this modest library of background information, we can now view the first of this month's ASCC Hotline topics through a custom lens...call it adjusted for perspective...and down into the rabbit hole we go...

Plain dobies (no tie wire) Dobies with tie wire